By Susan K. Parson

FAA Safety Briefing Editor

You are an instrument-rated pilot, preparing to fly an instrument-equipped airplane on a day when instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) require the use of both. You are flying from a non-towered airport, and weather conditions won’t allow departing under VFR. No problem. You find the right frequency or phone number and call clearance delivery. The controller rattles off a clearance in the familiar C-R-A-F-T (Clearance Limit, Route, Altitude, Frequency, Transponder Code) format and you copy it down.

You note a couple of instructions that differ from the IFR clearance you would get at a towered airport. You know the “hold for release” drill, because of course you can’t launch into IMC until air traffic control (ATC) ensures that you will have the required separation from other IFR traffic. The other phrase, issued just before the controller reads your route clearance, is “upon reaching controlled airspace ….”

Oh, Say Can You See?

Before you do anything else, you need to verify that you can depart the non-towered field and climb to the altitude where controlled airspace begins without hitting anything in your path. Hopefully you took that into account during preflight planning but avoiding a departure controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) accident requires one last review of your surroundings and your game plan. When I lived on the East Coast, I sometimes flew to a non-towered airport in the North Carolina foothills. The typical first fix in an IFR clearance was to a VOR that sat atop a nearby mountain. It was on me, as pilot in command, to avoid any terrain or other obstacles located along the immediate departure path. Depending on the runway in use and climb gradient, a simple straight-out departure to that mountaintop fix might not work out so well. So, what to do?

If Not, Use the ODP!

Here’s where having a solid command of the Aeronautical Information Manual’s (AIM) section on Instrument Departure Procedures (see AIM 5–2–9) is not just handy, but essential. Please read this entire section of the AIM carefully, but here are a few high points.

ODPs provide obstruction clearance via the least onerous route from the terminal area to the appropriate en route structure.

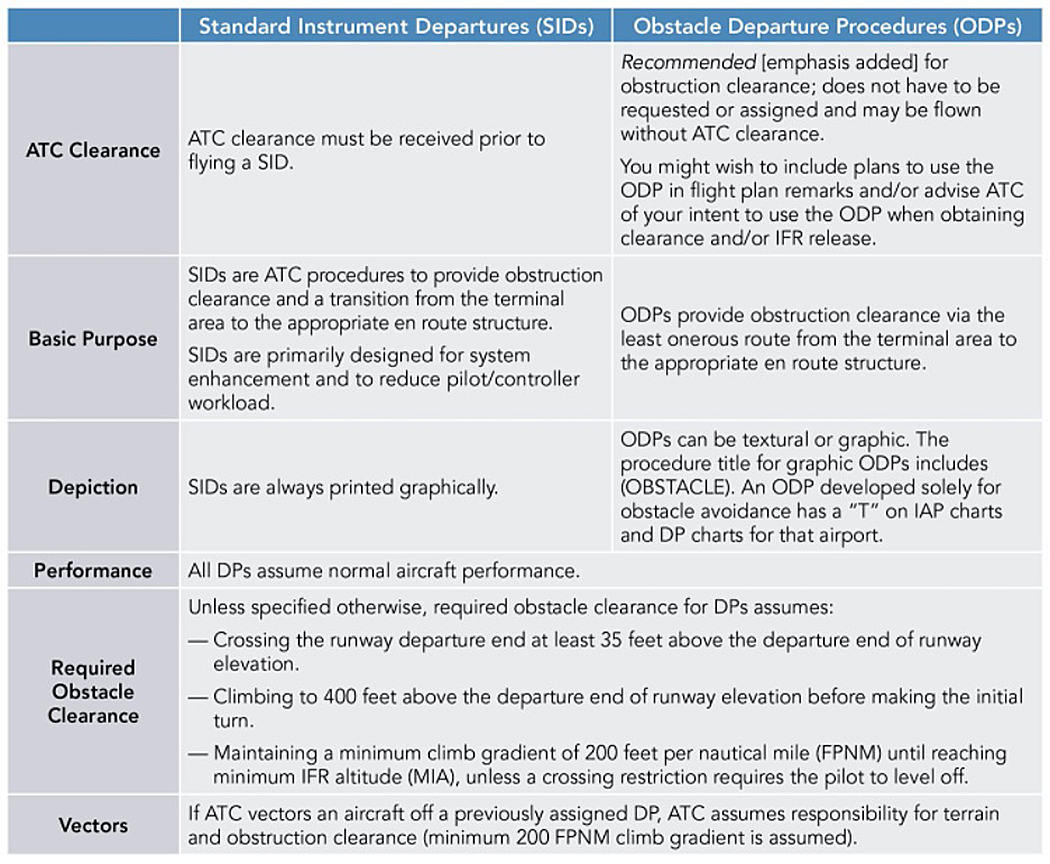

Departure Procedures (DPs) exist to provide obstacle clearance protection information to pilots. They come in two basic flavors. The one you might best remember is the Standard Instrument Departure (SID), used at busier towered airports to increase efficiency and reduce communications needs and departure delays. While SIDs might have an obstacle clearance function, it is entirely possible for a SID to exist only for ATC purposes. Either way, ATC will explicitly include a SID as part of your clearance.

That’s not the case for Obstacle Departure Procedures (ODPs), which are published for the purpose the very name expresses. There are several important things to know about ODPs, and it’s no exaggeration to say that your safety and your life could depend on having that knowledge. Table 1 (derived from the text of AIM 5–2–9) is intended to help you see some of the key differences more clearly.

DPs of a Different Sort

The AIM section on DPs also includes information on DVAs — Diverse Vector Areas — and VCOAs (Visual Climb Over Airport). In brief, a DVA is an area in which ATC may provide random radar vectors during an uninterrupted climb from the departure runway until above the Minimum Vectoring Altitude or Minimum IFR Altitude (MIA). The DVA provides obstacle and terrain avoidance in lieu of using an ODP or SID.

A VCOA procedure is a departure option for an IFR aircraft to visually conduct climbing turns over the airport to the published “climb-to” altitude from which to proceed with the instrument portion of the departure. Pilots must advise ATC of the intent to fly the VCOA option prior to departure.

Don’t Miss on the Missed Approach

The missed approach procedure (MAP) poses another CFIT hazard. It is one of the most challenging maneuvers a pilot can face, especially when operating alone (single pilot) in IMC. Safely executing the MAP requires a precise and disciplined transition that involves not only aeronautical knowledge and skill — the natural areas of focus in most training programs — but also a crucial psychological shift. There is little room for error on instrument missed approach procedures, and a pilot who hesitates due to deficits in procedural knowledge, aircraft control, or mindset can quickly become a CFIT statistic. Carefully study the MAP as part of your approach briefing, and don’t deviate from the published altitudes and headings.

Careful planning is the key to avoiding CFIT during IFR flight, especially during IMC operations.

See the Big Picture

Careful planning is the key to avoiding CFIT during IFR flight, especially during IMC operations. Before you even get to the airplane, you need to: (1) identify terrain and obstacles on or in the vicinity of the departure airport; (2) determine whether an ODP is available; (3) determine whether obstacle avoidance can be maintained visually or if the ODP should be flown; (4) consider the effect of degraded climb performance and the actions to take in the event of an engine loss during the departure; and (5) check the Terminal Procedures Publication for Takeoff Obstacle Notes. You’ll be glad you did.

Susan K. Parson (susan.parson@faa.gov) is editor of FAA Safety Briefing and a Special Assistant in the FAA’s Flight Standards Service. She is a general aviation pilot and flight instructor.

Reprinted with permission from FAA Safety Briefing at https://www.faa.gov/news/safety_briefing/